|

I am a Florida Keys Flats Fishing Guide. I have lived in Islamorada working full

time in the charter fishing business since 1975. I became a full time flats guide in 1977. Prior to that I worked on offshore charter boats fishing for sailfish, dolphin, tuna and any of the myriad species inhabiting the reef zone. In the seventies the backcountry guides were an exclusive clique who was universally suspicious of any outsiders. Even though I had worked several seasons on the offshore boats I was not immediately welcomed into the guiding community. The following is a description of the environment in which I, as a twenty-one year old outsider, was attempting to establish myself as a beginner guide. Click here to view some old photos. In 1977, Jack Kertz was the owner of Bud 'n' Mary's Marina in Islamorada. One day he took me aside on the dock to tell me that Jimmy Albright, Cecil Keith, and Clarence Lowe had met with him to state that I, along with Alex Adler and Sonny Eslinger, had to go. Jack said that Jimmy, who was speaking for himself and the other guides, was demanding that he throw us out of the marina. I was appalled - how could that be? I'd been around for over two years at that point. What had I done to deserve being ejected from Bud 'n' Mary's? And what was the need to toss Alex and Sonny as well? Alex had close associations with Jack through his father and Sonny had been around the marina for many years. I asked Jack, "What did you tell them?" He told me his reply to their demand was, "Hell no I'm not throwing those guys out - they're the only ones around here that pay their bills on time." What a relief, Jack not only stood by us, but he also went so far as to offer me a slip on the guide dock. Bouncer Smith had recently moved back to Miami and his slip had just become available. He suggested I should start guiding and that I should take advantage of the open slip - after all, there was no telling when another slip would become available. So, I took his advice, snapped up the slip, and entered the business of being a backcountry guide out of Bud 'n' Mary's Marina in Islamorada, in the Florida Keys. None of that that went over very well with the guides but they kept quiet and left me alone. Turns out the only reason they wanted Jack to throw us three out was simply because we were going live-bait tarpon fishing in the evenings down at the bridges. Prior to that the guides were the only people going evening tarpon fishing and there were never any cases when non-guides would venture down that far to try to get in on the evening action. That was because the return trip back to the dock after dark was tricky, and was not the province of amateurs. But since I was now a guide there was nothing they could say about me being down at the tarpon spots in the evenings. Actually, Sonny left the charter boat scene and started guiding at about the same time. And Alex, who had been working as a mate on the charter boats, got his own boat, the Kalex, and began his career as a charter boat captain at Bud 'n' Mary's. The guides made it a point to ignore me and that was fine with me. I was cognizant of the existence of the pecking order and my position on it. Therefore, I minded my business and stayed out of their way. That way they left me alone. One day I took one of my associates from the charter boat crews out in my skiff to fly fish for tarpon. He was one of the local characters; he was the son of one of the charter boat captains and had been around Bud 'n' Mary's all his life. He worked as a mate on the offshore boats and was well known. Even though he was born in Islamorada and raised around boats and fishing it was always the offshore environment he was in. He'd never been exposed to flats fishing, much less Florida Bay which was Terra Incognito as far as he was concerned. His given name was Wayne - but his moniker was "Skunk Ape" on account of the fact he was, you might say, a little rough around the edges. It always seemed to me that fly fishing on the flats was more of a "genteel" form of sport when compared to the offshore methods of trolling or chumming. Therefore, in order to explore the intriguing possibility of a link between fly fishing and anthropology, I ran a social experiment - I put Wayne in my skiff, took him into the backcountry, and then shoved a fly rod into his hand. As I recall we had a great day. Wayne caught a tarpon on the fly rod and was thrilled. But after I got back to the dock I detected murmuring amongst the old guides. Later one of them pulled me aside and gave me a stern but respectful lecture about taking charter boat mates out into what they considered to be their domain, of which they were protective to the extreme. Out of respect for their concerns and deference to their stature I followed their advice. Henceforth, I never took anyone into Florida Bay, the Islamorada backcountry, whom I thought the old time guides might perceive to be a threat. At that time I'd never heard of the author, Thomas McGuane. Later I learned that the manner in which the older guides maintained this collective protectiveness over the fishery that they had spent decades developing was actually the theme of the book, Ninety-Two in the Shade which was published in 1973, the year I graduated from high school. The guides at Bud 'n' Mary's were literally urbane compared to Nichol Dance, the antagonist in McGuane's book. The reason the guides were so protective was because the way that things were done, the code of etiquette, the knowledge that the health of the fishery depended on the flats being treated as refuges for the fish, and the awareness that the only way the flats could act as refuges was if disturbances from boat motors was kept at a minimum, and all this needed to be maintained for things to keep working. The only way to maintain any of that was to try to make sure everybody who used the resource understood these things. This was their strategy and it was a strategy which had been working just fine for decades. So, it was after I'd been working for a couple of years in this environment when I had a break- through. One day I was with clients who were not fly fishermen and wanted to catch a tarpon. Generally in that case we would use live bait. I got my folks in the boat and trundled on down to one of the bridges to float some mullet in the current near the bridge. When I got down to the bridge there was another guide already there. This wasn't a problem; there was plenty of room for both of us. I shut the motor off and drifted in to the spot where I planned to drop the anchor. I got anchored and got the baits in the water. The other guide was Earl Gentry from Bud 'n' Mary's. Earl was one of the old timers. At that point he was in his seventies and had been guiding since before time. Everything was good; we were waiting for a tarpon swim by and attack one of the mullet. Well, one of the mullet got attacked, but it wasn't a tarpon that did the attacking - it was an osprey. And of course, the osprey ended up getting hooked in one of its talons. I remember it was a hard falling tide and we had to bring the hooked, screeching osprey in against the current. I through a towel over the bird and removed the hook. I got the bird settled down and released it. I was expecting it to fly but it couldn't because its feathers were too wet from being drug in against the current. Instead it was swept through the bridge and out to sea by the tide, flapping all the way. Well, normally I would never have started my motor near Earl unless one of my clients had hooked a fish, but we didn't have anything hooked and the osprey was going to sea. I needed to do something. The bird was going to die, I needed to get moving and get it out of the water, and that is what I did. I dropped my anchor buoy, started the motor, raced after the osprey, used my landing net to get the bird in the boat, and brought the bird back through the bridge and set it in the sun on the wing-wall at the end of the bridge so it could dry out. Then I went back and retrieved my anchor and resumed fishing. I figured I'd catch some kind of flak for making so much engine noise but when Earl came up to me later at the dock he commended me for saving the bird. He said it was the noblest thing he'd ever seen. And that was the turning point. Before that Earl had never really spoken to me. But after that the guides all accepted me as someone who would uphold the etiquette and be a steward of the resource on which we all depended for our way of life, which was the life of a Florida Keys Flats Guide. |

|

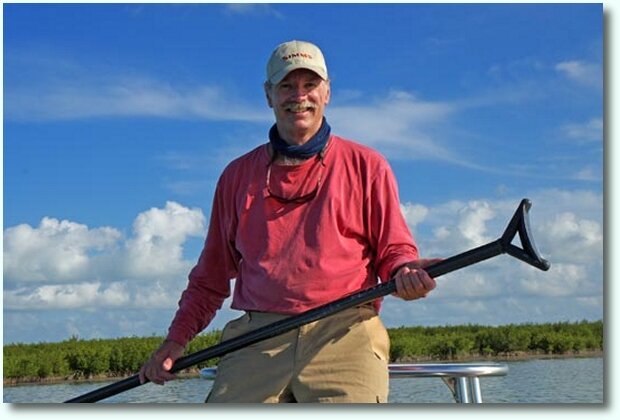

Photo courtesy Lori Oberhofer

|